A Framework for Advancing Health Equity in Neurology in the… : Neurology Today – LWW Journals

Article In Brief

The disproportionate burden of COVID-19 on Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities—with neurologic complications, in particular—makes it imperative for neurologists to focus on addressing disparities in access to care. Three neurologists involved in equity and diversity initiatives propose a framework for addressing those inequities.

The disproportionately higher rate of COVID-19 among marginalized populations, including members of the Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities, and the 35- to 85 percent prevalence of neurologic symptoms during the acute phase of their illness, and many extending the symptomatic period post-acutely to what sometimes is called “long COVID,” make it imperative for the neurology community to address the unequal burden of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, wrote the authors of a commentary in the January issue of Nature Medicine.

The disproportionate burden of COVID-19 provides an opportunity, as well, to address longstanding inequities in access to neurologic care and outcomes, said the three neurologists from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. To do so, they adapted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Health Impact Pyramid—which visually depicts the impact of different public health interventions—as a proposed framework for addressing these disparities.

“An anti-racist, patient- and community-centered approach must be adopted to identify, comprehensively understand and effectively treat the post-acute consequences of COVID-19, including neurological sequelae,” Harvard medical student LaShyra T. Nolen, MD; Shibani Mukerji, MD, PhD, and Nicte Mejia, MD, MPH, FAAN, wrote. “This requires shifting meaningful resources and power to marginalized communities most affected by COVID-19, while effectively applying a multi-level framework for public health action.”

As with the original CDC pyramid, strategies with the smallest personalized impact, such as counseling and clinical interventions, are placed at the top, while those with the most substantial foundational impact form the bottom layer of the pyramid.

“Everything in the pyramid matters, but as you go down, the strategies will take more time and more investment, but will have more impact,” said Dr. Mejia, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, director of MGH neurology community health, diversity and inclusion, and director of of the MGH youth neurology education and research program.

Counseling and Educational Efforts

At the top of the pyramid are counseling and educational efforts such as sharing prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and research information on COVID-19 and neurological health via trusted and engaged messengers in and for marginalized communities.

“First author LaShyra Nolen created the non-profit We Got Us project, which has diverse teams of health educators bringing trusted messengers to communities of color, holding roundtables, and providing educational materials about COVID-19, vaccination, and medical racism,” says Dr. Mejia. “They are making a difference here in Massachusetts, and there are similar groups in places like Philadelphia and New York.”

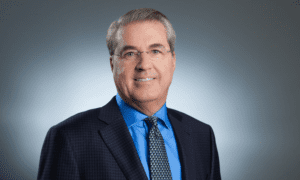

As another example, Columbia University Irving Medical Center has developed a community center on one of its new campuses in Harlem, said Mitchell S. Elkind, MD, MS, FAAN, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and chief of the division of neurology clinical outcomes research and population sciences (Neuro CORPS). “The center is nestled into the Harlem community, and as part of its programming trains lay people from the community as health workers. They then serve as trusted messengers that can provide outreach to the community.”

“We may not have universal health yet, but can allocate resources to support communities disproportionally affected by COVID-19, to help with everything from vaccine equity to post-acute care for people with long-term consequences, many of which are neurologic.”—DR. NICTE MEJIA

Clinical Interventions

The second level of the pyramid involves clinical interventions—in this context, access to neurology clinicians, neurodiagnostics, and neurotherapeutic resources in and for marginalized communities, which have historically had limited access to these resources. A 2017 Neurology study by Dr. Mejia, Altaf Saadi, MD, MSc, and colleagues, found that Black patients were nearly 30 percent less likely to see an outpatient neurologist compared with their White counterparts, while Hispanic patients were 40 percent less likely, despite having known neurologic conditions.

Expansion of telehealth services, which have been rapidly expanded because of the COVID-19 pandemic, is one way to improve access to neurologic care for people in underserved communities.

“We have been using telehealth more frequently to be able to reach patients who may be unable to visit the hospital or clinic,” said Dr. Elkind. “For example, one of our junior faculty, Imama Naqvi, MD, has developed and tested a multi-component program for stroke patients at discharge that includes remote home-based blood pressure monitoring, nursing and pharmacy intervention, and infographics to help patients understand the impact of blood pressure on their health. She has shown that this program can substantially reduce blood pressure in our Black and Hispanic patients.”

Preventive Interventions

In the middle of the pyramid, Dr. Mejia and colleagues place long-lasting preventive interventions (such as equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and personal protective equipment). Next is, changing the context to make individuals’ default decisions healthy, via legislative and policy provisions to achieve universal health care and other region-specific needs.”

“Here, my colleague and co-author Dr. Mukerji, taught me how there are things we can learn from the HIV epidemic,” said Dr. Mejia. “Recognizing gaps, the United States made the decision to invest in the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, which has been ongoing for some 30 years, to support programming aimed at preventing and treating HIV and then measuring the outcomes. When you look at who accesses those funds, we know that this program has positively affected the lives of many Black, Latino, and Native people. We may not have universal health care yet, but can allocate resources to support communities disproportionally affected by COVID-19, to help with everything from vaccine equity to post-acute care for people with long-term consequences, many of which are neurologic.”

“Neurologists need to more actively engage in advocating for their patients well-being outside the hospital and clinic. Our role in improving brain health can no longer be seen as something that occurs solely, or even primarily, in the exam room or interventional suite. It needs to happen by ensuring access to health insurance, providing education about healthy behaviors, and creating healthy communities where people can lead their healthiest lives.”—DR. MITCHELL S. ELKIND

At the base of the pyramid, the focus is on addressing fundamental socioeconomic and environmental factors such as equitable access to wealth, education, jobs, housing, transportation, and clean air and water.

What Neurologists Can Do

These recommendations can sound daunting to the individual neurologist. “It’s very easy to become overwhelmed and say ‘What is my role in this situation? I want to do something to help my patients, I know this is a crucial issue, I want to fit in here, but what is my piece?’” said Erika Marulanda, MD, associate program director of the neurology residency at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, where she is a member of the equity, diversity and inclusion committee.

“This article provides the impetus and framework to see places where you can fit in at multiple levels. First, we have to realize that it is our lane,” Dr. Marulanda said.

“We do have a role in addressing these inequities. See yourself as someone who can bring up these questions in your community, division or institution,” she continued. “Look around and see, day to day, what are the things that could be better for underserved patient populations in your area. And then you have to follow through to improve access to care. That can mean different things in different places. In a rural area, maybe it’s telemedicine. In other places, maybe it’s community health workers, community paramedics, and nurses to see patients at home to augment neurologists.”

If you have a leadership role in your institution or practice, Dr. Mejia added, you have resources and power that you can use to make a difference. “Who are you hiring and what communities are you hiring from? How well are you paying people?” she asked. “Are you opening our doors to provide meaningful opportunities for education? Here at Massachusetts General, we had long had the dream of expanding the opportunities the department of neurology offered for youth in our community to access neurology education and research training. When the pandemic started, we partnered with the Biogen Foundation to recruit and hire high school and undergraduate students from the Massachusetts communities most affected by COVID-19. The MGH Youth Neurology education and research program’s 60 alumni have embraced opportunities for paid mentored research over the summers of 2020 and 2021, deepening their interest in neuroscience and their commitment to pursue graduate education and careers with the potential to change their socioeconomic trajectory.”

Another much needed socioeconomic change is the expansion of access to health care coverage. “In our 2017 Neurology study that documented racial and ethnic disparities in access to outpatient neurologic care, we found that people who had Medicare or Medicaid coverage had access, but that people who were uninsured were about 60 oercent less likely to see outpatient neurologists,” Dr. Mejia said. “We know from Kaiser Family Foundation data that 31 million people remain uninsured in America today, and Black, Latino and Indigenous communities are really overrepresented in that group.”

“Its very easy to become overwhelmed and say ‘What is my role in this situation? I want to do something to help my patients, I know this is a crucial issue, I want to fit in here, but what is my piece?… This article provides the impetus and framework to see places where you can fit in at multiple levels. First, we have to realize that it is our lane.”—DR. ERIKA MARULANDA

Research from the University of Southern California published ahead of print in December 2021 in Lancet Health found that after four years of implementation, the expansion of Medicaid was associated with 12 fewer deaths per 100,000 adults annually—an overall drop of approximately 3.8 percent in adult deaths each year.

Dr. Mejia noted that some people who are uninsured may be eligible for health iinsurance, either via Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act, but they may not know how to apply or that they qualify. “These people may not be coming to our neurology clinics, but chances are they are coming to the emergency department,” she said. “As neurologists, when we attend on services that intersect with the ED, we need to be attuned to asking people about the challenges that brought them there. We need to reach residents to ask if someone has a primary care provider and if health insurance is an issue, and that when we learn of the gaps, it’s our duty to connect them with case workers and social workers.”

Of course, since the Supreme Court made Medicaid expansion optional for states, almost half opted out, and as of today, 12 states—primarily concentrated in the South and Midwest—still have not increased access to Medicaid, Dr. Mejia said.

“Neurologists may be able to have an impact working at the state level by partnering with your state neurological society, or even at the county or municipal level for places that have oversight of their local health system, to push for policy changes that will address some of these core fundamental issues,” said Charles C. Flippen, MD, FAAN, the Richard D. and Ruth P. Walter Professor of Neurology at UCLA, where he serves as director of the neurology residency program.

“An individual neurologist in a state that hasn’t expanded Medicaid should speak up,” Dr. Flippen advised. “Share patient stories. Share where we haven’t been able to render care. Telling those stories is valuable. That’s what helps persuade people, or at least gets them talking. We know these disorders, we know the patients who are affected by them, and the families impacted by their illness, and we can give voice to their stories in a way that others cannot.”

“Neurologists need to more actively engage in advocating for their patients’ well-being outside the hospital and clinic,” Dr. Elkind agreed. “Our role in improving brain health can no longer be seen as something that occurs solely, or even primarily, in the exam room or interventional suite. It needs to happen by ensuring access to health insurance, providing education about healthy behaviors, and creating healthy communities where people can lead their healthiest lives.”

He also calls for the AAN take a leadership role in educating neurologists about the importance of seeing our patients within the context of this holistic framework. “The AAN should also join with other major public health organizations, like the American Heart Association, to advocate for access to insurance and health care, healthy environments, and educational resources. We mustn’t forget where people go when they leave our offices, and how the environment in which they live for the much greater part of their time influences the choices they make.”

“Neurologists may be able to have an impact working at the state level by partnering with your state neurological society, or even at the county or municipal level for places that have oversight of their local health system, to push for policy changes that will address some of these core fundamental issues.”—DR. CHARLES C. FLIPPEN

“Maybe we can’t get 1000 ‘Dr. Smiths’ going to Washington, but can we get a group of ten to go to Sacramento or Austin?” Dr. Flippen asked. “I understand that in the setting of a pandemic that is entering its third year, everyone has reached their limit at some point, but we can’t continue to kick the can down the road. We’re stronger working together, so work through your local organizations and the AAN, which has a robust apparatus and has become the trusted voice on neurological disease when policymakers have questions. We have people’s ears; we just need to exercise our voices.”