Tracing the History of the Green Book in Southern California

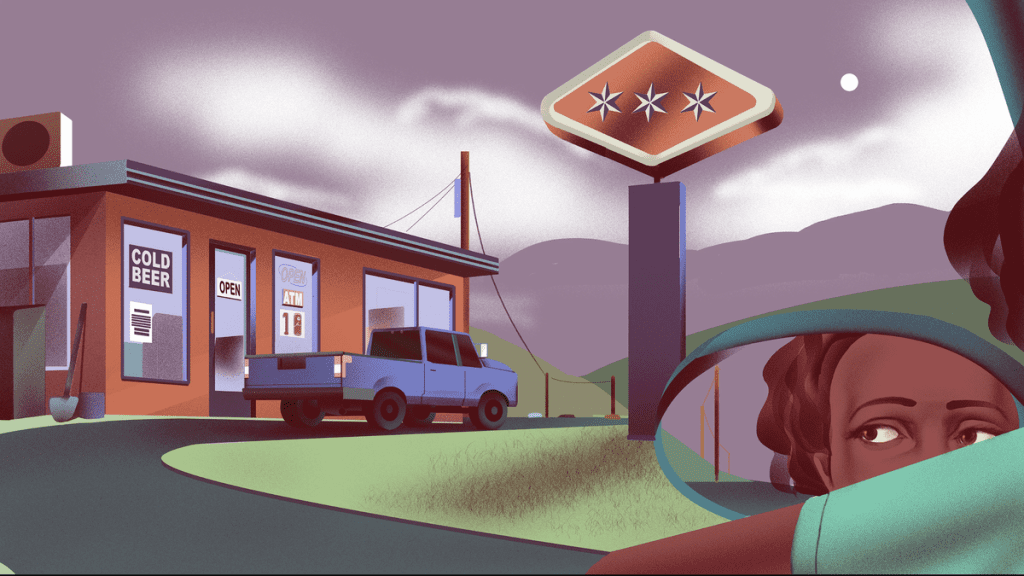

Being drivers in the 21st century, modern technology has allowed us to have tons of information at our disposal. From travel times with ETAs that are accurate down to the minute to real-time traffic information, many of us take these conveniences for granted. It wasn’t always this way, as those of us who used to print out Mapquest directions recall. But consider that, just over half a century ago, paper maps and travel guides existed to keep certain portions of the population safe while they were out driving. The Negro Traveler’s Green Book, sometimes known as The Negro Motorist Green Book, was that guide. For 30 years, it provided information to help Black drivers navigate America’s roads safely.

Jalopnik has written about the Green Book in the past, and the 2018 movie Green Book informed a new generation of the existence of these guides. California alone had more than 80 businesses listed in the Green Book over the years — restaurants, hotels, gas stations and more, all known for being friendly to Black travelers. I wanted to dig deeper, to find out if any of these businesses were still around today.

Published from 1936 to 1966, The Negro Travelers Green Book was printed annually and distributed to Black people across the country. The guide was the brainchild of Victor Hugo Green, a travel writer and U.S. Postal Service mailman. The idea for the guide came to him in the 1930s, when he began collecting information on New York City motels, gas stations, and other businesses that were safe for Black travelers to visit.

The Green Book was largely unknown to white Americans, but it was huge within the Black community. A surprising sponsorship deal with Standard Oil resulted in the book being sold in Esso gas stations across the U.S.

A 1949 edition of the travel guide, archived in the New York Public Library. Image: New York Public Library

Today, it might seem strange that Black people would need their own travel guide just to move around within the United States. But think of the time when the Green Book was published. This was Jim Crow America. Racial segregation laws ruled the country, especially in southern states. Simply stopping to buy gas or ask for directions could get a Black person killed.

As America began building modern interstate highways after World War II, it was important for Black travelers to know where they could safely go for food, fuel or lodging. The Green Book listed businesses in over 300 cities in the U.S. and Canada where Black customers were welcome.

While most of the businesses listed were located in major cities, the Green Book also held information on how to safely travel through smaller towns. In locations where businesses were hostile to Black travelers, the book often gave addresses for private homes where travelers could stay the night.

California often had the largest number of listings that would welcome Black travelers. The number of locations in the state would fluctuate a bit from year to year, but not by much — in a 1957 edition of the guide, for instance, the Golden State boasts 81 locations that were safe for Black road trippers. That same issue had 97 businesses listed in New Jersey and 91 in Michigan. Even Texas had over 90 locations.

I wondered — were any of those California businesses still around today? I hit the road to find out.

The street of a former location from the guide in Lake Elsinore, CaliforniaScreenshot: Google Maps

Sadly, many of the Green Book locations that were local to me are long gone. The addresses are still there, but many of the hotels, restaurants and gas stations have become entirely different establishments from what was once listed in the guide. For instance, a location that was once called the Lake Elisnore Hotel in Lake Elsinore, California is just a residential street now. Other locations have ceased to exist entirely, right down to the address. A motel in Riverside called El Camino Motel is gone, and I couldn’t find a trace of its existence. The reason? It’s now a street that crisscrosses fields on March Air Force Base.

So I left the Inland Empire to try my luck in Los Angeles.

The Lincoln Hotel as it looks today on Skid Row in Los Angeles. Screenshot: Google Maps

The Lincoln Hotel is one of the many addresses listed in L.A. While it once housed Black travelers, today the Lincoln Hotel is a mainstay on the city’s Skid Row, a business that has helped thousands of people over the years get back on their feet.

Image: CBS Youtube

One of the most famous locations in Los Angeles, both for Black travelers in the Jim Crow era and history buffs today, is Clifton’s Cafeteria. When it closed in 2018 it was the oldest cafeteria in the city and the largest public cafeteria in the world. Unfortunately, gentrification got the better of it, and today the location is a fancy hipster bar called Clifton’s Republic.

Many of the addresses from the Green Book that still exist today are unremarkable residential locations. But in my travels around L.A., a few stood out.

The Aster Hotel as it appears today.Screenshot: Google Maps

The Aster Motel still sits along the 110 freeway, just over a mile from the University of Southern California’s L.A. campus. You’d hardly even know it’s there, sitting behind a few other buildings. While the Aster was once a haven for Black travelers, it has a grim history. Just a year after the motel opened, in 1947, the motel landed at the center of a gruesome murder case that got national attention through sensational newspaper coverage. This was the murder of Elizabeth Short, also known as the Black Dahlia murder.

Short’s naked body was discovered in a vacant lot in the Leimert Park neighborhood on January 15th, 1947. She had allegedly been staying in Room 3 at the Aster Motel; the motel’s owner reported that, on the morning Short’s body was discovered, Room 3 was found covered in blood. At the time, the LAPD presented a different theory, alleging that Short was never a guest at the Aster Motel; the 2017 book Black Dahlia, Red Rose resurfaced the alleged connection between Short and the motel.

Another Green Book site has a rich and much lighter history. The Dunbar Hotel was at the heart of Black culture in L.A. in the early 20th century. People described it as a “West Coast mixture of the Waldorf-Astoria and the Cotton Club.” The Dunbar hosted the biggest Black stars — Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday — and gave a home to the west coast NAACP convention. Although it was deemed a historic and cultural monument in the early 1970s, by the 1980s the hotel had fallen into ruin. In 2011, the Dunbar and its adjacent buildings were purchased and redeveloped into a mixed-use, integrated community called Dunbar Village, with 83 housing units split between 41 affordable units and 41 senior units.

Including the three listed above, just 10 Los Angeles-area Green Book sites are still standing today, out of nearly 30 that were listed when the book was in publication. It’s sad to see so few left, and to think of the stories that could be told by the places that aren’t around anymore.

America has gotten better since the Green Book ceased publication in 1966, in the sense that Black motorists don’t need to rely on a guidebook to find businesses that won’t turn them away. It’s sad to think of an era when the Green Book had to exist, but I find it inspirational to look back on the businesses and families listed in those pages. It’s a bittersweet feeling to know that, in the depths of Jim Crow discrimination, Black travelers could find a safe haven in places where most businesses wouldn’t accept them, thanks to a book put together by people who wanted Black Americans to safely experience the joy and freedom of the modern road trip.