Johnny Walklate: the rare scooter

Johnny Walklate was in his mid 20s when he moved to Italy, for a girl.

While that relationship didn’t work out, over three years living in Viareggio, on the coast north of Pisa, he met and fell in love with one of the country’s finest exports – scooters.

Both his dad and grandad had owned Lambrettas before he was born, but Johnny’s first taste of two wheels came on a 50cc Vespa ET2 he used to get to and from work, initially as a chef.

“That started my passion for scooters and learning about the history,” he says. “It was my first venture of freedom – I could go anywhere I wanted, do anything I wanted, and I discovered the love of the older models as well. You used to see them floating about, the old Vespas and stuff.

“Because you can get a 50cc moped out there when you’re 14, the roads are full of scooters. It’s a totally different way of life in scootering.”

Birthplace of Vespa

By happy coincidence, Pontedera, the birthplace of Vespa, is a mere 35 miles southeast of Viareggio – and Johnny would regularly ride his scooter down to the Piaggio museum.

“I’d go and spend a few hours looking at all the old machines and all the prototypes they’ve got down there, and visit the different exhibitions they put on during the year,” he says.

But it was Milan’s Lambretta that would truly capture his heart and lead to an enduring fascination with everything Innocenti, especially the rare, unusual, or early scooters.

Johnny’s rare Lambretta Model A (left), and Model B

Johnny’s rare Lambretta Model A (left), and Model B

After a period collecting Lambretta 48 autocycles and the Luna scooter range, he finally landed his personal Holy Grail – a 1948 Model A, Innocenti’s first ever scooter.

“It was always my dream to have a first model Lambretta,” he says, at his home in Leicestershire, “but I always said I’d have to sell everything else to get one.”

So the four autocycles and three Lunas were moved on, with only the 1950 Model B bought several years earlier remaining.

Compulsive collecting

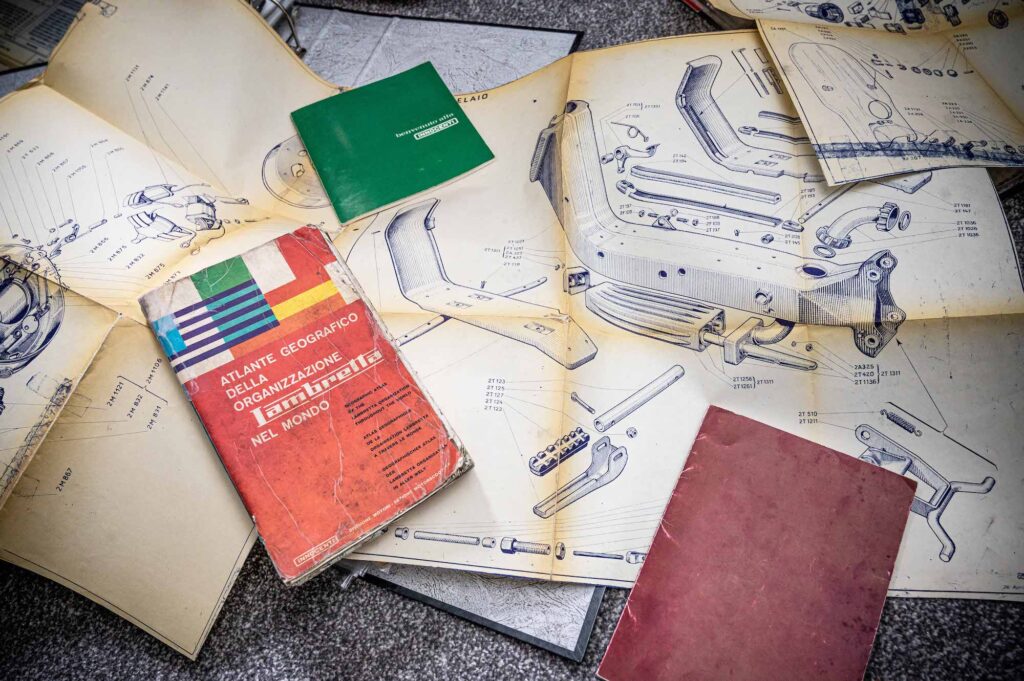

“I’ve always had a fascination for things that aren’t as common – they kind of catch my attention,” he says, which also extends to an almost compulsive desire to gather as much documentation relating to the scooters and the Innocenti factory as possible.

“It’s just a quest for knowledge and my obsessive nature. I enjoy hunting things down and trying to find something new and it literally got out of hand – it really did.

A tiny part of Johnny’s collection

A tiny part of Johnny’s collection

“The biggest side of the paperwork collection is the user manuals. My quest was to find one for every machine that Innocenti ever made for Lambretta, including the autocycles and three wheelers. There’s just the one machine to go now, and that’s the first ever three wheeler they made, the FB model, but they only made 2,001 machines.

“Very few of those survive – I know of 12 in the world, so the chances of finding a book are very slim. But never say never! I do have the parts catalogue for it, which is a bonus.”

And then there’s the Lambretta Frame Check service, born in 2018 in collaboration with Pete Davies, who founded the British Lambretta Archive in 2002.

Lambretta frame check service

Using Johnny’s original factory documents, the frame check service allows anyone to find out the build month of their Lambretta.

“It seemed logical for me to utilise my archive to help other people,” he says.

But back to Italy and 2004, and Johnny swapped life in the kitchens for work as a polisher in the boatyards, working on the superyachts built in Viareggio.

It was there that he got his first Lambretta, a late ‘60s J50 bought from his boss.

“That’s what set my life on a course of really getting involved with Lambrettas,” he says. “You don’t really see J50s about, because they’re low powered, but they’re lovely little machines and have a cult following.”

When he returned to the UK in September 2007, both the J50 and Vespa ET2 came with him.

“Me and my brother went on a five and a half day trip in the van to bring back all my belongings,” he remembers. “We drove all the way there and back and had a laugh, ate some good food and drank some good wine.”

The ET2 was quickly replaced by a brand new, 2008 Vespa 50S, which became his commuter scooter to and from work back in a restaurant kitchen – “there’s a distinct lack of boatyards around here, in the middle of the country!”.

After a couple of years, during which Johnny passed his bike test, the J50 was replaced by a Lambretta GP150, unfortunately written off when an off-duty police officer knocked him off on his way home from work one night.

Polishing and restoring

A GP200 followed, and Johnny used his spare time to polish and restore old Lambretta parts.

“I rented a unit and that sort of took off,” he says, “and then I started doing three days a week working for some friends at TheLambro.com, restoring the three wheeler Lambros.”

This led to “picking trips” to Italy, and the beginning of Johnny’s autocycle and Luna collection.

“We went to a place on the Adriatic coastline just south of Rimini, fetching the three wheelers back,” he says, “and one guy had also got a load of old scooters in a chicken coop in this sort of builders quarry yard.

“I took some cash with me, just in case there was anything cheap going, and I pulled out a little Lui (Luna) 50C which turned out to be quite a unique model because of its colour and production date.

Johnny’s Lambretta Luna collection

Johnny’s Lambretta Luna collection

“In the first month of production of the Lui range, they were only available in white, but several were done in an aquamarine blue, and mine was an original paint orange.

“I’d seen an orange one in a book once, but this was the first one that had come to light and been found in its original orange.”

The 50C was soon joined by a 50CL – fitted with Casa performance parts – and a 75S, marketed in the UK as the Vega.

Lambretta 48

Johnny’s quest for Lambrettas seldom seen on the UK’s roads, but which are also affordable, led him to the comparatively little-known Lambretta 48 range.

Introduced at the Milan Show in 1954, the 48 was a two-stroke, two-speed moped named after its engine size.

“At the end of the day, they’re an affordable model,” he says. “I’ve never grown up having money, and moving around as much as I did in my younger days, I never made a home anywhere – I was always pissing money up the wall renting.

“So it was great having the opportunity to drop on some of these models that aren’t necessarily going to break the bank.”

Johnny’s first 48 was picked up by his Lambro.com colleague Ian near the border with Croatia.

The four Lambretta 48s

The four Lambretta 48s

“He went out to pick up a frame we needed and he said ‘if there’s anything on the way or the way back you want picking up, let me know’,” he says. “I found this autocycle on the internet, did the deal and Ian picked it up and brought it back for me. It was something ridiculous like €160, not a lot of money.

“It barely ran, had been hand painted with emulsion at some point, and wasn’t the nicest example, but what do you expect for that kind of money?”

Three more autocycles

It seemed reasonable to ask why he then bought three more…

“Strange question,” he laughs. “There was a big collection in Italy that Dean Orton, who formerly owned Rimini Lambretta Centre, cleared out of northern Italy.

“One was a really nice Lambretta 48 that ended up going to an elderly gentleman down in Hastings. He had had it a number of years and I had a whisper he was thinking of letting it go. “We struck a deal and had a weekend away down there to collect it. It was museum quality and won me a couple of awards at shows. I used to ride that one around and it was really fun.

“I then found a first series 48 in the Rimini area, and very few of those have survived or are known to exist. It was in really rough condition but, again, it was ridiculously cheap.

“The last one was on another trip to Italy, from an older gentleman who lived near the Lambretta factory. It had probably never been more than a few kilometres from the factory until it came to me. It still ran in its original paint and condition.

“It wasn’t a case of going out there and searching for a lot of this stuff – you get known to be into a certain niche, and people get in touch with you.”

A few years ago, Johnny was in the unusual position of having a little cash to spend, and sold the GP200 to help fund the purchase of the 1950 Model B from someone in Worksop.

Fixation with early Lambrettas

“I’d got such a fixation with the earlier stuff and thought at the time I’d never be able to afford a Model A,” he says, “So it was the next best thing for me, and it’s done its job, it’s given me a lot of fun over the years and still does.

“That’s probably the one I’d ride the most when I had the whole collection, commuting to work, nipping up town, riding around the countryside.

“It’s not the quickest machine, but it’s not about that, it’s about enjoying something that’s built with 1940s technology and engineering and, 70 years on, it’s still going.”

It was on the Model B that Johnny completed his longest ride in recent years, from Manchester to Sheffield and back across Snake Pass.

“That was an interesting ride, and a lot of fun,” he says. “We were all on early model shaft driven Lambrettas with eight inch wheels. It was a good test for the scooter, hill climbing on an old machine like that. It was probably quicker walking!”

Models A and B look very different to most people’s idea of a Lambretta, especially as Johnny’s B has a period racing fuel tank.

“The B draws a lot of interest because it’s a model that a lot of people haven’t really seen before, and they don’t see them on the roads,” he says. “There are not so many in the country, especially ones that get used. There are quite a few in pristine conditions that only ever get wheeled out and taken to shows, but I’ve always liked to ride and make sure that everything I’ve got runs and is usable.

“Some Sundays I’d make a day of it and I’d go and do 20 miles on one machine, come back, swap machines, do another 20 miles, and keep swapping throughout the day. By the end, you’ve done 100 miles on five bikes.”

Packed in like Sardines

With nine scooters and autocycles crammed into his single garage, Johnny, now 44, admits that things “quickly got out of hand”.

“The logistics of getting them out of the garage when they’re all in there like sardines took some working out,” he says. “If you’re going to ride to work, you had to sort it out the night before so you’re not getting up at 6.30am and getting eight out of the way.

“There comes a time when you think ‘do I want to sell a few off and get something that I really want?’, and that happened two years ago when I had a big clear out.

“After I’d sold all the other machines and was just left with the Model B, I decided I was going to start looking for a Model A.”

The Holy Grail was within sight, the first scooter to come from the Innocenti factory that had previously been used to manufacture scaffolding poles.

Ferdinando Innocenti rejected a design for a spar-framed scooter by Corradino D’Ascanio because he wanted to produce the scooter’s frame from rolled tubing instead, thereby utilising the factory’s tooling and expertise.

D’Ascanio promptly took his design to Piaggio and the Vespa was born in 1946, a year before Innocenti finally got the tube-framed Model A off the ground.

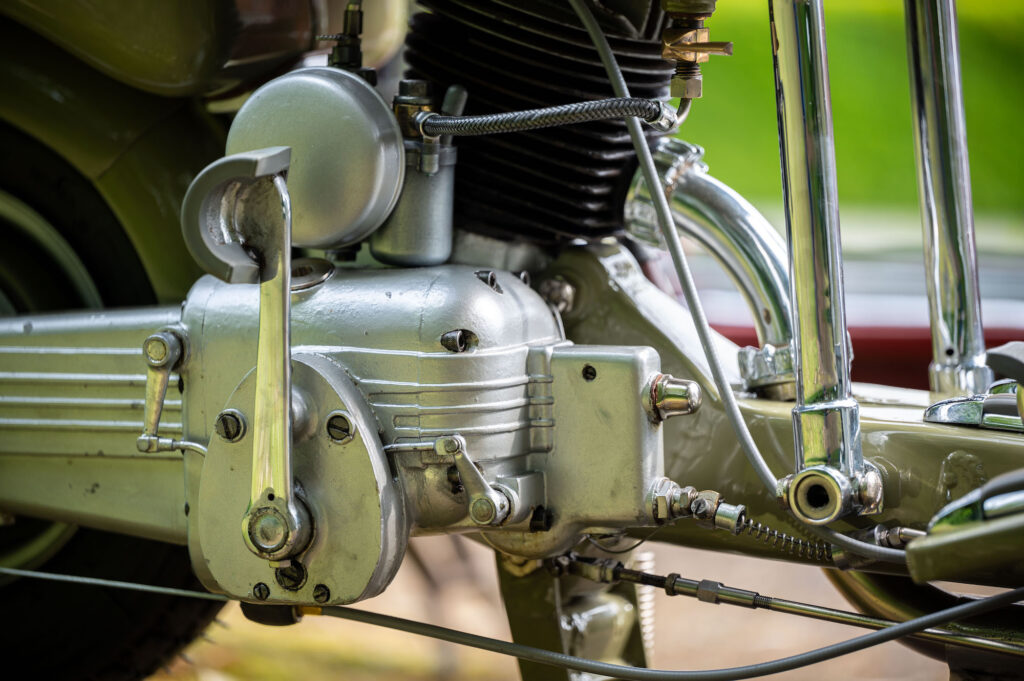

Featuring a 123cc shaft-driven, direct air-cooled engine, the three-speed Model A used tiny seven-inch wheels and had no rear suspension other than the seat springs – at the front, just two rubber bushes cushioned the forks.

A total of just 9,669 were manufactured in the 12 months from October 1947, before the Model B took over.

Holy Grail Model A in sight

Johnny’s search left him with a choice of three of the “20 or 30” Model As known to be in the UK.

“One with parts missing in somebody’s attic, and another that was complete but – looking at the photos – for what was being asked was not a viable option,” he says.

“The third option was this rolling chassis with all its correct parts from an elderly gentleman called Howard Chambers, who was quite a renowned fellow on the scootering scene in the UK, especially for the early machines. Sadly, he died in January.

1940s technology

1940s technology

“He took me to one of his lock ups and there it was in all its cheese grater glory. It was all there, and the price was fine, but it did need a lot of work.”

That work is nearing its end after nearly two years, the scooter back in its original olive green paintwork, with just some electrical work to be completed.

“I’m not an expert at the electrical side of things, and I’d rather just get someone else to do it,” he says, “and then get someone with mechanical knowledge just to go over it one final time for me, and then I’ll get it going.

“I’m led to believe they are superior to the Model B – they are supposed to have upgraded to that, but took some of the power out a bit. Apparently the A is so much more fun, so I look forward to the day I get mine going, this summer hopefully.”

Mission accomplished?

It almost feels like mission accomplished for Johnny – he has the scooter he always longed for, and the one he’s arguably had the most fun riding.

So now he plans to focus on filling in the gaps on a collection of documents valued somewhere between £15,000 and £20,000.

“These things have gone up in value a lot in recent years,” he says. “There are a lot more people collecting the leaflets and brochures, and they are commanding higher prices.

“A lot of these things never get advertised for sale, they just get exchanged behind closed doors in gentlemen’s agreements.

“When a collection down at Weston-super-Mare was recently being sold off, there were a couple of gems there that I hadn’t got and I needed, so I managed to jump in and get what I was missing.

“The Model A parts catalogue is mega rare and set me back £500 just for that one. I wasn’t the only interested party in that. I spent the best part of £1,000 on three items!

“Things come from all over the world. I’ve got a Model B user manual in English, which is super rare – I know of only one other – and it came from Maine in America of all places. It’s even got the American distributor’s stamp on it from way back then.

The story of Innocenti

“I think, collectively, the whole lot tells a story and tells the history of the machines and the company as a whole.

“It’s not just the stuff that I like either, it’s anything related to the factory. So I’ve got staff handbooks that employees would have got when they started their job, books they’d give to visitors on factory tours, and a really old photographic book of the old machinery plant when they first started in the ‘30s in Milan – the first ever factory.

“Plus the story of them designing the machines to make scaffolding tubes and designing the modern scaffolding clamp. And it all relates to the scooters.

“I think that learning is a good thing, and it tells the history. A lot of people can write a book and put their version of the history there, but when you’ve got actual factory documents, that’s fact as it happened.”

As well as the documents, there is a patented Innocenti scaffolding clamp and a brick from the now disused factory on Johnny’s sideboard, solid memorabilia that adds flavour to his collection of paper artefacts.

Scooter stories is a series of articles exploring the lives and experiences of different types of scooter riders and collectors. More stories will be added in the coming months. Click on the Scooter Stories category link to read more.